During World Cup, Sachin, Unwell, Was Told His Father Had Died

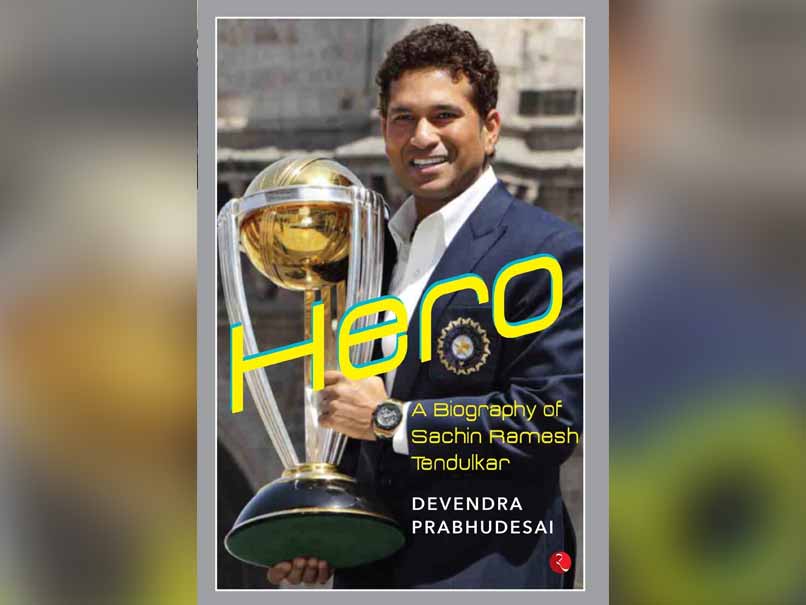

Exclusive excerpt from 'Hero: A Biography of Sachin Ramesh Tendulkar' by Devendra Prabhudesai.

- Devendra Prabhudesai

- Updated: April 24, 2017 12:00 pm IST

The hype in India on the eve of the first World Cup to be played in England since Kapil’s Devils lifted the trophy at Lord’s on 25 June 1983 was to be experienced to be believed. The logic doing the rounds was that India would win the 1999 tournament because it had won the previous edition to be played in England. For once, even the cynical sections of the media played along with this bizarre reasoning, totally disregarding the recent failures of the team.

The obsession with the upcoming tournament was not restricted to the cricketing community. Almost every brand of note tweaked its advertising strategies to create a connect with cricket. The build-up culminated with an exhibition game between the Team of 1983 and the Team of 1999. Almost every brand sought to jump onto the cricketing bandwagon through its advertising campaigns, and every media outlet of note brought out a ‘Special Issue’ on the tournament.

One periodical listed ‘11 reasons why India would win the World Cup’. Reason number one was, not surprisingly, Sachin, who was ‘fully fit’, as per the writer. The fact was that he wasn’t. But then, missing the World Cup was out of the question. So Sachin did what he could in terms of training. To combat the stiffness of his back, he resorted to sleeping on the floor of his hotel room with a pillow below his knees, to ensure that his back stayed flat on the ground.

The presence of Sachin Tendulkar should be an inspiration for everyone. The likes of Rahul Dravid and Sourav Ganguly should take over the mantle, and reduce the pressure on him. — Mohammed Azharuddin, The Sportstar, 15 May 1999

India did not start very well, losing their first match to South Africa at Hove. The team hoped to get things back on track in their second fixture against Zimbabwe at Leicester.

On the eve of the game, Sachin was with his friend Atul Ranade in his hotel room, when the bell rang. He opened the door to find Anjali standing in the corridor, flanked by Ajay Jadeja and Robin Singh. She had driven from London to Leicester late in the night to convey a terrible piece of news. Ramesh Tendulkar, the professor, philosopher and poet, was no more. The man who had penned the start of one of cricket’s most glorious chapters in the summer of 1984 by allowing his 11-year-old son to change schools, had suffered a fatal heart attack.

Prof. Tendulkar had not been keeping well over the previous few months and had undergone an angioplasty. After the procedure, he had temporarily moved in with Sachin, who by this time had shifted from Sahitya Sahawas to an apartment on the western side of Bandra. With Anjali supervising her father-in-law’s recuperation personally, things had started looking up. Sachin was relieved to see his father returning to normalcy, slowly and steadily. Hence, the news of the demise came as a shock.

The Tendulkars flew back to Mumbai early in the morning. At the funeral, which was attended by Prof. Tendulkar’s friends, colleagues, associates, neighbours, students and scores of individuals whose lives he had enriched over the years, Sachin kept a gold coin bearing his image in the shirt pocket of the man who meant everything to him. Life for him would never be the same again.

Even as Sachin was grieving, his teammates did not do their World Cup prospects any good by losing to Zimbabwe by a mere three runs. This meant that they had lost two matches out of two. With three league matches to go, their only hope of qualifying for the Super Six, the stage before the semi-finals, was to win all three. The BCCI and team management were clear in their stand on Sachin; they had decided to respect his privacy and decision.

It was Sachin’s mother, whose loss was bigger than Sachin’s, who urged her youngest son to fly back to England. Convincing Sachin was not that difficult, as he too knew that that was exactly what his father would have liked him to do. For the fans, the news that Sachin was returning to England to try and resurrect his team’s floundering campaign in the World Cup provided them with one of those hair-standing-on-end moments that make a lifetime of following the sport seem worthwhile.

He received a standing ovation on his arrival at the wicket during the next game against Kenya at Bristol, and he received another one on his dismissal after scoring 140 off only 101 deliveries, inclusive of 12 boundaries and three sixes. Coming in at number four, he batted exhilaratingly in the company of Dravid, who scored an unbeaten 104.

A moment that left watchers with a lump in their throats was when Sachin completed three figures and looked up, towards the heavens; it was one of the most poignant moments they had ever witnessed on a cricket field. India finished with a mammoth 329–2 and won by 94 runs.

Sachin did not have do much in the next game against Sri Lanka at Taunton.

He was once again designated to bat at number four, and he watched admiringly as Ganguly and Dravid annihilated the bowling. Both scored gigantic hundreds and added a record 318 for the second wicket. As Dravid had been designated wicketkeeper for the game, with Mongia missing due to injury, his 145 made him only the second wicketkeeper–batsman after Zimbabwe’s Dave Houghton to score a hundred in the World Cup.

Excerpted with permission of Rupa Publications India from Hero: A Biography of Sachin Ramesh Tendulkar by Devendra Prabhudesai. Available in bookstores and online.